God prosper long our noble Queen,

And long may she reign!

Maclean he tried to shoot her,

But it was all in vain.

For God He turned the ball aside

Maclean aimed at her head;

And he felt very angry

Because he didn’t shoot her dead.

There’s a divinity that hedges a king,

And so it does seem,

And my opinion is, it has hedged

Our most gracious Queen.

Maclean must be a madman,

Which is obvious to be seen,

Or else he wouldn’t have tried to shoot

Our most beloved Queen.

Victoria is a good Queen,

Which all her subjects know,

And for that God has protected her

From all her deadly foes.

She is noble and generous,

Her subjects must confess;

There hasn’t been her equal

Since the days of good Queen Bess.

Long may she be spared to roam

Among the bonnie Highland floral,

And spend many a happy day

In the palace of Balmoral.

Because she is very kind

To the old women there,

And allows them bread, tea, and sugar,

And each one get a share.

And when they know of her coming,

Their hearts feel overjoy’d,

Because, in general, she finds work

For men that’s unemploy’d.

And she also gives the gipsies money

While at Balmoral, I’ve been told,

And, mind ye, seldom silver,

But very often gold.

I hope God will protect her

By night and by day,

At home and abroad,

When she’s far away.

May He be as a hedge around her,

As he’s been all along,

And let her live and die in peace

Is the end of my song.

The Attempt on the Life of the Queen

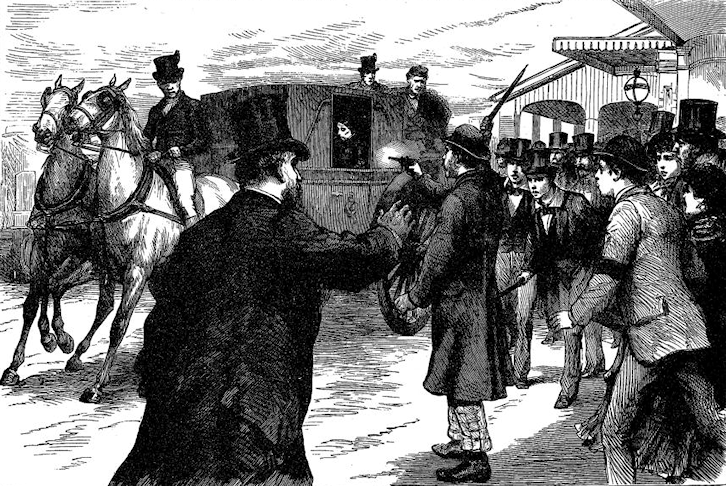

INTENSE horror and alarm were created all over the country by the news that on Thursday last week an attempt had been made to shoot the Queen, but the assurance which was at the same time circulated that Her Majesty had escaped unhurt tended greatly to allay the excitement, and perhaps to lessen the universal feeling of indignation which the crime had excited. The intelligence that the Queen had not even been much alarmed by the occurrence which had so startled every one else in the kingdom was in itself a relief to her anxious people, and a perfect flood of congratulatory messages was poured into Windsor from corporations and representative societies, as well as from individuals belonging to all classes of society, in all parts of the three kingdoms, as well as telegrams from the colonies and foreign countries. The story of the crime is soon told. Her Majesty on reaching Windsor had left the train, and with Princess Beatrice had seated herself in a carriage drawn by a pair of greys, and the vehicle had just, started when the miscreant, Maclean, who was standing in the front row of spectators, drew a revolver from his breast, and fired. At the same instant, however, Mr. Superintendent Hayes, Mr. James Burnside, a local photographer, and several Eton boys rushed forward, and he was disarmed and arrested, whining pitifully to his captors to protect him from the just indignation of the crowd. Her Majesty’s carriage was driven on towards the Castle as though nothing had happened, but the Queen’s first care was to inquire as to the safety of her attendants, and her next to send cheerful telegrams to the Prince of Wales and the Premier, lest exaggerated reports might be circulated. The prisoner was examined next day before the Windsor magistrates, and remanded until yesterday (Friday), being removed to Reading Gaol in the interim. From the evidence already taken it seems that the revolver was loaded with ball cartridge in three chambers, one of which only was fired, the bullet probably passing in rear of the Royal carriage as it was driven by, and, after striking against a railway truck, burying itself in the earth beyond, from whence it has since been recovered. Fourteen ball cartridges were also found in the possession of the prisoner, who, being examined by the police surgeon, was declared to be sane. Since then, however, a number of statements as to his family and former career have been published, which, if true, can leave little doubt that he is a lunatic. When arrested he was in a wretched condition, and his own statement is that hunger drove him to the commission of the crime; though with a cunning which is perhaps indicative of madness he denies that he had any desire to do more than alarm the Queen, and thus call attention to what he considers to be his wrongs. Mad or sane, he appears to have been a lazy, loafing scoundrel, for whom no sympathy can possibly be felt; and, if any crumb of consolation can be found amid the sad circumstances of the case, it is that the dreadful crime so happily averted was not the outcome of any political disaffection. It is to be hoped that we shall profit by the lesson recently set us by our American cousins in the trial of Guiteau, and dispose of Maclean as quickly and quietly as possible.

The Graphic, 11th March 1882

Notes

Queen Victoria was leaving Windsor railway station when a young man stepped forward from the cheering crowd, lifted a revolver and fired into her carriage. Before a second shot could be fired, the man was overpowered by the crowd and arrested by Superintendent Hayes of the Windsor Police. Remaining calm, the Queen and her companions rode on to Windsor Castle.

This assassination attempt, which took place on the 2nd March 1882, was the last of eight such attempts made during her long reign. The would-be assassin turned out to be a scotsman called Roderick Maclean. Like McGonagall, Maclean was a budding poet who had sent a loyal address to her Majesty. Unlike McGonagall however, he saw the polite “thanks but no thanks” letter he received in reply as an affront to his poetic sensibilities and resolved to be avenged. He was tried for high treason but found “not guilty but insane” and sent to an asylum. Victoria’s annoyance at this verdict caused the passing of an act the following year which changed the form of such verdicts to “guilty but insane”.

McGonagall’s poem is just one example of the outpouring of enthusiasm, loyalty, sympathy and affection for the Queen from her subjects. As Victoria subsequently wrote to her eldest daughter, “It is worth being shot at – to see how much one is loved”.

As well as his own moral indignation, McGonagall drew on two other sources when composing this poem. The first line of the third stanza is an allusion to a line in Hamlet, Act IV, scene 5:

There’s such divinity doth hedge a king,

That treason can but peep to what it would.

The details of Victoria’s magnanimity towards the poor and needy are drawn almost verbatim from what he was told on his journey to Balmoral four years earlier.

Further Reading

- The men who tried to kill Queen Victoria – An article from the Daily Express

Books

- Shooting Victoria: Madness, Mayhem, and the Modernisation of the British Monarchy – A history of the eight assassination attempts on the Queen, and what they tell us of Victorian society

- Kill the Queen! – Another history of the Queen’s would-be assassins

Today’s one across is a Scots poet’s name,

“considered one of the worst ever” – what shame!

Oh cruel Guardian to make this disdainful claim,

and slander so noble McGonagall’s famed name.

Nice little poem. I wonder how different Maclean’s poetry was?

Of all the world’s rhymsters abominable

‘Tis often said that the worst is McGonagall,

So when in the Guardian we now read

That he’s only “one of the worst”, this is praise indeed!

My favorite McGonnagall stanza of all:

“For God He turned the ball aside

Maclean aimed at her head;

And he felt very angry

Because he didn’t shoot her dead.”

Yes — God reflexively reached out his hand after hearing “God save the Queen” sung as Victoria arrived at the station, but was instantly angry with himself for it.

To be fair, Phil, I think he meant that Maclean was angry, rather than the Almighty – but who knows?