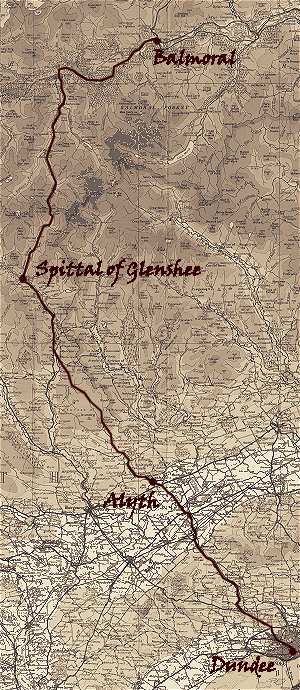

My dear readers, the next strange adventure in my life was my journey to Balmoral to see the bonnie Highland floral and Her Gracious Majesty the Queen, who was living in Balmoral Castle, near by the River Dee. Well, I left Dundee in the month of June, 1878. I remember it was a beautiful sunshiny day, which made my heart feel light and gay, and I tramped to Alyth that day, and of course I felt very tired end footsore owing to the intense heat. The first thing I thought about was to secure lodgings for the night, which I secured very easily without any trouble, and then I went and bought some groceries for my supper and breakfast, such as tea, sugar, butter, and bread. Then I prepared my supper, and ate heartily, for I had not tasted food of any kind since I had left Dundee, and the distance I had travelled was fifteen miles, and with the fresh air I had inhaled by the way it gave me a keen appetite, and caused me to relish my supper, and feel content. Then the landlady of the house, being a kind-hearted woman, gave me some hot water to wash my feet, as she thought it would make my feet feel more comfortable, and cause me to sleep more sound. And after I had gone to bed I slept as sound as if I’d been dead, and arose in the morning quite refreshed and vigorous after the sound sleep I had got. Then I washed my hands and face, and prepared my breakfast, and made myself ready for the road again, with some biscuits in my pocket and a pennyworth of cheese. I left, Alyth about ten o’clock in the morning, and crossed over a dreary moor, stunted and barren in its aspect, which was a few miles in length — I know not how many — but I remember there were only two houses to be met with all the way, which caused me to feel rather discontented indeed. The melancholy screams of the peesweeps overhead were rather discordant sounds ringing in my ears, and, worst of all, the rain began to fall heavily, and in a short time I felt wet to the skin; and the lightning began to flash and the thunder to roar. Yet I trudged on manfully not the least daunted, for I remembered of saying to my friends in Dundee I would pass through fire and water rather than turn tail, and make my purpose good, as I had resolved to see Her Majesty at Balmoral. I remember by the roadside there was a big rock, and behind it I took shelter from the rain a few moments, and partook of my bread and cheese, while the rain kept pouring down in torrents. After I had taken my luncheon I rose to my feet, determined to push on in spits of rain and thunder, which made me wonder, because by this time I was about to enter

Well, I left Dundee in the month of June, 1878. I remember it was a beautiful sunshiny day, which made my heart feel light and gay, and I tramped to Alyth that day, and of course I felt very tired end footsore owing to the intense heat. The first thing I thought about was to secure lodgings for the night, which I secured very easily without any trouble, and then I went and bought some groceries for my supper and breakfast, such as tea, sugar, butter, and bread. Then I prepared my supper, and ate heartily, for I had not tasted food of any kind since I had left Dundee, and the distance I had travelled was fifteen miles, and with the fresh air I had inhaled by the way it gave me a keen appetite, and caused me to relish my supper, and feel content. Then the landlady of the house, being a kind-hearted woman, gave me some hot water to wash my feet, as she thought it would make my feet feel more comfortable, and cause me to sleep more sound. And after I had gone to bed I slept as sound as if I’d been dead, and arose in the morning quite refreshed and vigorous after the sound sleep I had got. Then I washed my hands and face, and prepared my breakfast, and made myself ready for the road again, with some biscuits in my pocket and a pennyworth of cheese. I left, Alyth about ten o’clock in the morning, and crossed over a dreary moor, stunted and barren in its aspect, which was a few miles in length — I know not how many — but I remember there were only two houses to be met with all the way, which caused me to feel rather discontented indeed. The melancholy screams of the peesweeps overhead were rather discordant sounds ringing in my ears, and, worst of all, the rain began to fall heavily, and in a short time I felt wet to the skin; and the lightning began to flash and the thunder to roar. Yet I trudged on manfully not the least daunted, for I remembered of saying to my friends in Dundee I would pass through fire and water rather than turn tail, and make my purpose good, as I had resolved to see Her Majesty at Balmoral. I remember by the roadside there was a big rock, and behind it I took shelter from the rain a few moments, and partook of my bread and cheese, while the rain kept pouring down in torrents. After I had taken my luncheon I rose to my feet, determined to push on in spits of rain and thunder, which made me wonder, because by this time I was about to enter

On the Spittal of Glenshee,

Which is most dismal for to see,

With its bleak and rugged mountains,

And clear, crystal, spouting fountains

With their misty foam;

And thousands of sheep there together doth roam,

Browsing on the barren pasture most gloomy to see.

Stunted in heather, and scarcely a tree,

Which is enough to make the traveller weep,

The loneliness thereof and the bleating of the sheep.

However, I travelled on while the rain came pouring down copiously and I began to feel very tired, and longed for rest, for by this time I had travelled about thirteen miles, and the road on the Spittal of Glenshee I remember was very stony in some parts. I resolved to call at the first house I saw by the way and ask lodgings for the night. Well, the first home chanced to be a shepherd’s, and I called at the door and gently knocked, and my knock was answered by the mistress of the house. When she saw me she asked me what I wanted, and I told her I wanted a night’s lodging and how I was wet to the skin. Then she bade me come inside and sit down by the fireside and dry my claes, and tak’ aff my shoon end warm my feet at the fire, and I did so. Then I told her I came from Dundee, and that I was going to Balmoral to see Her Majesty the Queen, and that I was a poet. When I said I was a poet her manner changed altogether and she asked me if I would take some porridge if she made some, and I said I would and feel very thankful for them. So in a short time the porridge were made, and as quickly partaken, and in a short time the shepherd came in with his two collie dogs, and the mistress told him I was a traveller from Dundee and a poet. When he heard I was a poet he asked me my name, and I told him I was McGonagall, the poet. He seemed o’erjoyed when be heard me say so, and told me I was welcome as a lodger for the night, and to make myself at home, and that he had heard often about me. I chanced to have a few copies of a twopence edition of poems with me from Dundee and I gave him a copy, and he seemed to be highly pleased with reading the poems during the evening, especially the one about the late George Gilfillan, and for the benefit of my readers I will insert it as follows. I may also state this is the first poem I composed, when I received the gift of poetry, which appeared in the “Weekly News” :–

LINES IN PRAISE OF THE REV. GEORGE GILFILLAN

All hail to the Rev. George Gilfillan, of Dundee,

He is the greatest preacher I did ever hear or see.

He preaches in a plain, straightforward way,

The people flock to hear him night and day,

And hundreds from his church doors are often turned away,

Because he is the greatest preacher of the present day.

The first time I heard him speak ’twas in the Kinnaird Hall,

Lecturing on the Garabaldi movement as loud as he could bawl.

He is a charitable gentlemen to the poor while in distress,

And for his kindness unto them the Lord will surely bless.

My blessing on his noble form and on his lofty head.

May all good angels guard him while living and hereafter when dead.

Well, my dear readers, after the shepherd and me had a social confab together concerning Gilfillan and poetry for some time his wife came in, and she said, “Guidman, I’ve been out making a bed for you in the barn. But maybe ye’ll be feared tae sleep in the barn.” But I said, “Oh, no, my good woman, not in the least.” So she told her husband to show me the way to the barn, and he said, “Oh, yes, I’ll do that, and feel, highly honoured in doing so.” Accordingly he got a lantern and lighted it, and then said — “Come along with me, sir, and I’ll show you where to sleep for the night.” Then he led the way to the barn, and when he entered he showed me the bed, and I can assure you it was a bed suitable for either King or Queen.

And the blankets and sheets

Were white and clean,

And most beautiful to be seen,

And I’m sure would have pleased Lord Aberdeen.

Then the shepherd told me I could bar the barn door if I liked if I was afraid to sleep without it being barred, and I said I would bar the door, considering it much safer to do so. Then he bade me good-night, hoping I would sleep well and come in to breakfast in the morning.

A Strange Dream

After the shepherd had bidden me good-night I barred the door, and went to bed, as I expected to sleep; but for a long time I couldn’t — until at last I was in the arms of Morpheus, dreaming I was travelling betwixt a range of mountains, and seemingly to be very misty, especially the mountain tops. Then I thought I saw a carriage and four horses, and seemingly two drivers, and also a lady in the carriage, who I thought would be the Queen. Then the carriage vanished all of a sudden, and I thought I had arrived at Balmoral Castle, and in front of the Castle I saw a big Newfoundland dog, and he kept barking loudly and angry at me but I wasn’t the least afraid of him, and as I advanced towards the front door of the Castle he sprang at me, and seized my right hand, and bit it severely, until it bled profusely. I seemed to feel it painful, and when I awoke, my dear readers, I was shaking with fear, and considered it to be a warning or a bad omen to me on my journey to Balmoral. But, said I to myself —

“Hence babbling dreams!

You threaten me in vain.”

Then I tried hard to sleep, but couldn’t. So the night stole tediously away, and morning came at last, peeping through the chinks of the barn door. So I arose, and donned my clothes, then went into the shepherd’s house, but the shepherd wasn’t in. He’d been away two hours ago, the mistress said, to look after the sheep on the rugged mountains. “But sit ye down, guidman,” said she, “and I’ll mak’ some porridge for ye before ye tak’ the road, for it’s a dreary road to Balmoral”. So I thanked her and husband for their kindness towards me, and telling her to give my best wishes to her husband bade her good-bye and left the shepherd’s house for the Queen’s Castle.

It was about ten o’clock in the morning when I left the shepherd’s house at the Spittal of Glenshee on my journey to Balmoral. I expected to be there about three o’clock in the afternoon. Well, I travelled on courageously, and, when Balmoral Castle hove in sight, I saw the Union Jack unfurled to the breeze. Well, I arrived at the Castle just as the tower clock was chiming the hour of three. But my heart wasn’t full of glee, because I had a presentiment that I wouldn’t succeed. When I arrived at the lodge gate, I knocked loudly at the door of the lodge, and it was answered by a big, burly-looking man, dressed in a suit of pilot cloth. He boldly asked me what I wanted and where I had come from. I told him I had travelled all the way from Dundee expecting to see Her Majesty, and to be permitted to give an entertainment before her in the Castle from my own works and from the works of Shakespeare. Further, I informed him that I was the Poet McGonagall, and how I had been patronised by Her Majesty. I showed him Her Majesty’s letter of patronage, which he read, and said it was a forgery. I said, if he thought so, he could have me arrested. He said this thinking to frighten me, but, when he saw he couldn’t, he asked me if I would give him a recital in front of the Lodge as a specimen of my abilities. “No, sir,” I said; “nothing so low in my line of business. I am not a strolling mountebank that would do the like in the open air for a few coppers. Take me into one of the rooms in the Lodge, and pay me for it, and I will give you a recital, and upon no consideration will I consent to do it in the open air.”

It was about ten o’clock in the morning when I left the shepherd’s house at the Spittal of Glenshee on my journey to Balmoral. I expected to be there about three o’clock in the afternoon. Well, I travelled on courageously, and, when Balmoral Castle hove in sight, I saw the Union Jack unfurled to the breeze. Well, I arrived at the Castle just as the tower clock was chiming the hour of three. But my heart wasn’t full of glee, because I had a presentiment that I wouldn’t succeed. When I arrived at the lodge gate, I knocked loudly at the door of the lodge, and it was answered by a big, burly-looking man, dressed in a suit of pilot cloth. He boldly asked me what I wanted and where I had come from. I told him I had travelled all the way from Dundee expecting to see Her Majesty, and to be permitted to give an entertainment before her in the Castle from my own works and from the works of Shakespeare. Further, I informed him that I was the Poet McGonagall, and how I had been patronised by Her Majesty. I showed him Her Majesty’s letter of patronage, which he read, and said it was a forgery. I said, if he thought so, he could have me arrested. He said this thinking to frighten me, but, when he saw he couldn’t, he asked me if I would give him a recital in front of the Lodge as a specimen of my abilities. “No, sir,” I said; “nothing so low in my line of business. I am not a strolling mountebank that would do the like in the open air for a few coppers. Take me into one of the rooms in the Lodge, and pay me for it, and I will give you a recital, and upon no consideration will I consent to do it in the open air.”

Just at that time there was a young lady concealed behind the Lodge door hearkening all the time unknown to me. The man said, “Will you not oblige the young lady here?” And when I saw the lady I said, “No, sir. Nor if Her Majesty would request me to do it in the open air, I wouldn’t yield to her request.” Then he said, “So I see, but I must tell you that nobody can see Her Majesty without an introductory letter from some nobleman to certify that they are safe to be ushered into Her Majesty’s presence, and remember, if ever you come here again, you are liable to be arrested.” So I bade him good-bye, and came away without dismay, and crossed o’er a little iron bridge there which spans the River Dee, which is magnificent to see. I went in quest of lodgings for the night, and, as I looked towards the west, I saw a farmhouse to the right of me, about half a mile from the highway. To it I went straightaway, and knocked at the door gently, and a voice from within cried softly, “Come in.” When I entered an old man and woman were sitting by the fireside, and the man bade me sit down. I said I was very thankful for the seat, because I was tired and footsore, and required lodging for the night, and that I had been at Balmoral Castle expecting to see Her Majesty, and had been denied the liberty of seeing her by the constable at the Lodge gate. When I told him I had travelled all the way on foot from Dundee, he told me very feelingly he would allow me to stay with him for two or three days, and I could go to the roadside, where Her Majesty passed almost every day, and he was sure she would speak to me, as she always spoke to the gipsies and gave them money. The old woman, who was sitting in the corner at her tea, said, “By, and mind ya, guidman, it’s no silver she gives them, it’s gold. I’m sure Her Majesty’s a richt guid lady. Mind ye, this is the Queen’s bread I’m eating. Guidman, the mair, I canna see you. I’m blind, born blind, and I maun tell ye, as you’re a poet, as I heard ye say, the Queen alloos a’ the auld wimmen in the district here a loaf of bread, tea, and sugar, and a’ the cold meat that’s no used at the Castle, and, mind ye, ilka ane o’ them gets an equal share.” I said it was very kind of Her Majesty to do so, and she said, “That’s no’ a’, guidman. She aye finds wark for idle men when she comes here– wark that’s no needed, no’ for hersel, athegether, but just to help needy folk, and I’m sure if you see her she will help you.” So I thanked her for the information I had got, and then was conducted to my bed in the barn– a very good one– after I had got a good supper of porridge and milk. Then I went to bed, not to sleep, but to think of the treatment I had met with from the constable at the lodge of Balmoral Castle. I may state also that I showed the constable at the lodge a copy of my poems — twopence edition — I had with me, and he asked me the price of it, and I said, “Twopence, please.” Then he chanced to notice on the front of it, “Poet to Her Majesty,” and he got into a rage and said, “You’re not poet to Her Majesty.” Then I said, “You cannot deny that I am patronised by Her Majesty.” Then he said, “Ah, but you must know Lord Tennyson is the real poet to Her Majesty. However, I’ll buy this copy of your poems.” But, as I said before, when I went to bed it was to think, not to sleep, and I thought in particular what the constable told me– if ever I chanced to come the way again I would be arrested, and the thought thereof caused an undefinable fear to creep all over my body. I actually shook with fear, which I considered to be a warning not to attempt the like again. So I resolved that in the morning I would go home again the may I came. All night through I tossed and turned from one side to another, thinking to sleep, but to court it was all in vain, and as soon as daylight dawned I arose and made ready to take the road. Then I went to the door of the farmhouse and knocked, and it was answered by the farmer, and he said, “‘Odsake, guidman, hoo have ye risen sae early? It’s no’ five o’clock yet. Gae awa’ back to your bed and sleep twa or three hours yet, and ye will hae plenty o’ time after that tae gang tae the roadside to see Her Majesty.” But I told him I had given up all thought of it, that I was afraid the constable at the lodge would be on the lookout for me, and if he saw me loitering about the roadside he would arrest me and swear falsely against me. Then he said, ” Guidman, perhaps it’s the safest way no’ to gang, but, however, you’ll need some breakfast afore ye tak’ the road, sae come in by and sit doon there.” Then he asked me if I could sup brose, and I said I could, and be thankful for the like. Then he cried, ” Hi! lassie, come here and bile the kettle quick and mak’ some brose for this guidman before he gangs awa’.” Then the lassie came ben. She might have been about sixteen or seventeen years old, and in a short time she had the kettle boiling, and prepared for me a cog of brose and milk, which I supped greedily and cheerfully, owing no doubt to the pure Highland air I had inhaled, which gave me a keen appetite. Then the farmer came ben and bade me good-bye, and told me to be sure and call again if ever I came the way, and how I would be sure to get a night’s lodging or two or three if I liked to stay. So I bade him good-bye and the lassie and the old blind woman, thanking them for their kindness towards me. But the farmer said to the lassie,” Mak’ up a piece bread and cheese for him for fear he’ll no’ get muckle meat on the Spittal o’ Glenshee.” So when I got the piece of bread and cheese again I bade them good-bye, and took the road for Glenshee, bound for Dundee, while the sun shone out bright and clear, which did my spirits cheer. After I had travelled about six miles, my feet got very hot, and in a very short time both were severely blistered. So I sat me down to rest me for a while, and while I rested I ate of my piece bread and cheese, which, I’m sure, did me please, and gave me fresh strength and enabled me to resume my travel again. I travelled on another six miles until I arrived at a lodging-house by the roadside, called the Miller’s Lodging-House because he had been a meal miller at one time. There I got a bed for the night, and paid threepence for it, and I can assure ye it was a very comfortable one; and the mistress of the house made some porridge for me by my own request, and gave me some milk, for which she charged me twopence. When I had taken my porridge, she gave me some hot water in a little tub to wash my feet, because they were blistered, and felt very sore. And when my feet were washed I went to my bed, and in a short time I was sound asleep. About eight o’clock the next morning I awoke quite refreshed, because I had slept well during the night, owing to the goodness of the bed and me being so much fatigued with travelling. Then I chanced to have a little tea and sugar in my pocket that I had bought in Alyth, so I asked the landlady if she could give me a teapot, as I had some tea with me in my pocket, and I would infuse it for my breakfast, as I hadn’t got much tea since I had left Dundee. So she gave me a teapot, and I infused the tea, and drank it cheerfully, end ate the remainder of my cheese and bread. I remember it was a lovely sunshiny morning when I bade my host and hostess good-bye, and left, resolved to travel to Blairgowrie, and lodge there for the night. So I travelled on the best way I could. My feet felt very sore, but

As I chanced to see trouts louping in the River o’ Glenshee,

It helped to fill my heart with glee,

And to anglers I would say without any doubt

There’s plenty of trouts there for pulling out.

When I saw them louping and heard the birds singing o’erhead it really seemed to give me pleasure, and to feel more contented than I would have been otherwise. At Blairgowrie I arrived about seven o’clock at night, and went in quest of a lodging-house, and found one easy enough, and for my bed I paid fourpence in advance. And when I had secured my bed I went out to try to sell a few copies of my poems I had with me from Dundee the twopence edition, and I managed to sell half a dozen of copies with a great struggle. However, I was very thankful, because it would tide me over until I would arrive in Dundee. So with the shilling I had earned from my poems I bought some grocery goods, and prepared my supper — tea, of course, and bread and butter. Then I had my feet washed, and went to bed, and slept as sound as if I’d been dead. In the morning I arose about seven o’clock, and prepared my breakfast– tea again, and breed and butter. Then after my breakfast I washed my hands and face, end started for Dundee at a rapid pace, and thought it no disgrace. Still the weather kept good, and the sun shone bright and clear, which did my spirits cheer, and weary and footsore I trudged along, singing a verse of a hymn, not a song, as follows :–

Our poverty and trials here

Will only make us richer there,

When we arrive at home, &c., &c.

When at the ten milestone from Dundee I sat down and rested for a while, and partook of a piece bread and butter. I toiled on manfully, and arrived in Dundee about eight o’clock, unexpectedly to my friends and acquaintances. So this, my dear friends, ends my famous journey to Balmoral. Next morning I had a newspaper reporter wanting the particulars regarding my journey to Balmoral, and in my simplicity of heart I gave him all the information regarding it, and when it was published in the papers it caused a great sensation. In fact, it was the only thing that made me famous — it and the Tay Bridge poem. I was only one week in Dundee after coming from Balmoral when I sent a twopence edition of my poems to the late Rev. George Gilfillan, who was on a holiday tour at Stonehaven at the time for the good of his health. He immediately sent me a reply, as follows :–

Stonehaven, June, 1878.

Dear Sir,– I thank you for your poems, especially the kind lines addressed to myself. I have read of your famous journey to Balmoral, for which I hope you are none the worse. I am here on holiday, but return in a few days.– Believe me, yours truly,

GEORGE GILFILLAN.

Well, the next stirring event in my life which I consider worth narrating happened this way.

Dan Canizares

I found a great…