He Refuses a “Lum” Hat

Proposed Statue

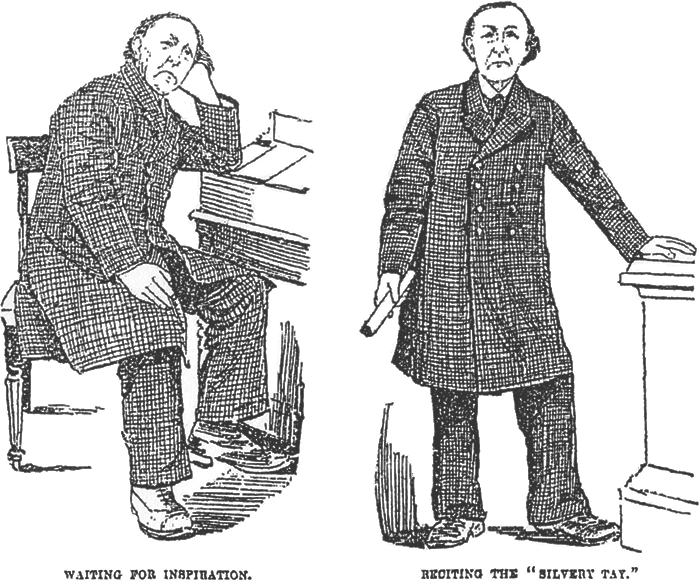

The Poet in his New Tweeds

Mr William McGonagall, poet and tragedian, 48 Step Row, Dundee, was on Wednesday presented with an address, a “lum” hat (which he returned with thanks), a walking stick and a purse of money by a number of his admirers in the city. The idea was suggested by the public presentation some time ago of a suit of Hawick tweeds, in the full glory of which McGonagall appeared. As a matter of fact, his friends in this case formed. a Sub-Committee of the Hawick Tweed Committee, if the term is allowable. A gentleman with a literary twist occupied the chair, being supported on the right by the Poet, and on the left by Mr John Saunders. There was a good attendance. The Chairman explained at the outset that the friends present were there to protest against the persecution of the Poet by boys and others, who, when he was seen on the street, advised him to get his hair cut. (“Shame.”) Yes, I say shame, repeated the Chairman. “Whoever heard tell of a poet with his hair cut? I ask you, gentlemen, did you ever hear of any poet with his hair cut?” (Voices— “Never,” and applause.) He then referred to some of McGonagall’s most beautiful pieces, such as “The Newport Railway” and “The Silvery Tay,” and concluded by handing him a nicely-mounted stick. The Poet suitably replied, remarking that he accepted “this beautiful stick, do you understand?” as a testimony to his abilities. The Chairman called for three cheers for the Poet’s abilities to which the response was hearty and unanimous. “The gentleman on his left,” said the Chairman, referring to Mr Saunders, would say a few words. Mr Saunders set a face of flint against the method of those “clarky-parky kind of fellows” who annoyed McGonagall. He and McGonagall were old “pals,” he said, but he was there not because of the friendship existing between them, but because he recognised the poetic measure of McGonagall, which had never actually been measured, although the meat offerings from the public had been many, but not always pleasant. McGonagall then recited the “Rattling Boy from Dublin Town,” the “whacks”, in the chorus being emphasised by “whacks” on the floor. He followed it up with his ode in honour of

The beautiful railway bridge of the silvery Tay

Most handsome to be seen, near by Dundee and the Magdalen Green

“The gentleman on the left” was again in evidence. He commenced this time by saying he was a “bit” of a poet himself, and if there were time at the close he would show the difference between McGonagall’s poetry and his, and from the comparison he would make they would observe that the Poet would win hands down. (Great laughter.) Proceeding, he read an address from the Committee recognising McGonagall as the “Poet Laureate” of the city and burgh of Dundee, and authorising him to go wherever he pleased and whenever he pleased, provided he conformed to the law. McGonagall replied that, although he took the address as a guarantee of protection he held it was impossible for the meeting to protect him when the constabulary of Dundee was unable to do so. The Saviour of Mankind told him that the only way he could secure protection was, “When you are persecuted in one city flee to another.” He continued— “If I was trusting to the protection of any gentleman in the company I am afraid I would fall to the wall. So says McGonagall!” (Cries of “Inspiration,” and loud applause.) The Poet was assured on all hands that he would be protected where possible and that there was present one of the strongest men in the city, who was prepared to tackle any tormentor. On the repetition of this assurance, the Poet waxed wroth, and threatened he would stand on his dignity and retire. He was latterly mollified, and gave “Bannockburn” in characteristic style. The Chairman then handed the poet a purse of money – the freewill offering of the audience – the purse having been perfumed with petroleum to an extent sufficient almost to stifle a regiment. The Poet hoped this would make him more contented with his lot. Following this, Mr Saunders here entertained the company with a series of Scotch, English and Irish songs, with the object of showing the difference between them and the writings of the city bard. As a finish, he handed the Poet a silk hat, alleged to have been the one which Gladstone wore when introducing one of his most important measures. McGonagall, however, intimated that he never wore and never intended to wear such a hat, and, while recognising the kindness thus displayed, refused to accept it. The meeting accordingly resolved that the hat should be returned and the value of it handed to McGonagall. After the Poet had given a full scene from Macbeth, the Chairman intimated that McGonagall had expressed a desire to have his portrait painted by an artist of the highest order, and with this object photographs of him in two positions had been secured. He was satisfied that this was necessary, so that if at any time a public statue might be erected there would be no difficulty in securing his classic features. We give representations of the photographs below.

Weekly News, 25th March 1893

Notes

A “lum hat” was a narrow-brimmed form of top hat, traditionally worn by bridegrooms in the area. McGonagall’s reluctance to accept such a gift is perhaps explained by his experiences in the streets of Dundee. He had enough trouble with the local boys without wearing a tall hat for them to knock off or throw stones at.