’TWAS in the month of December, and in the year 1883,

That a monster whale came to Dundee,

Resolved for a few days to sport and play,

And devour the small fishes in the silvery Tay.

So the monster whale did sport and play

Among the innocent little fishes in the beautiful Tay,

Until he was seen by some men one day,

And they resolved to catch him without delay.

When it came to be known a whale was seen in the Tay,

Some men began to talk and to say,

We must try and catch this monster of a whale,

So come on, brave boys, and never say fail.

Then the people together in crowds did run,

Resolved to capture the whale and to have some fun!

So small boats were launched on the silvery Tay,

While the monster of the deep did sport and play.

Oh! it was a most fearful and beautiful sight,

To see it lashing the water with its tail all its might,

And making the water ascend like a shower of hail,

With one lash of its ugly and mighty tail.

Then the water did descend on the men in the boats,

Which wet their trousers and also their coats;

But it only made them the more determined to catch the whale,

But the whale shook at them his tail.

Then the whale began to puff and to blow,

While the men and the boats after him did go,

Armed well with harpoons for the fray,

Which they fired at him without dismay.

And they laughed and grinned just like wild baboons,

While they fired at him their sharp harpoons:

But when struck with,the harpoons he dived below,

Which filled his pursuers’ hearts with woe.

Because they guessed they had lost a prize,

Which caused the tears to well up in their eyes;

And in that their anticipations were only right,

Because he sped on to Stonehaven with all his might:

And was first seen by the crew of a Gourdon fishing boat

Which they thought was a big coble upturned afloat;

But when they drew near they saw it was a whale,

So they resolved to tow it ashore without fail.

So they got a rope from each boat tied round his tail,

And landed their burden at Stonehaven without fail;

And when the people saw it their voices they did raise,

Declaring that the brave fishermen deserved great praise.

And my opinion is that God sent the whale in time of need,

No matter what other people may think or what is their creed;

I know fishermen in general are often very poor,

And God in His goodness sent it drive poverty from their door.

So Mr John Wood has bought it for two hundred and twenty-six pound,

And has brought it to Dundee all safe and all sound;

Which measures 40 feet in length from the snout to the tail,

So I advise the people far and near to see it without fail.

Then hurrah! for the mighty monster whale,

Which has got 17 feet 4 inches from tip to tip of a tail!

Which can be seen for a sixpence or a shilling,

That is to say, if the people all are willing.

The Whale Hunt in the Tay

Exciting Chase

“Nemo me impune lacesit,” each whaler remarked after his whaleship’s derisive dance on Sunday. Being touched in a vital part by his scornful gestures, they determined on revenge, and had the opportunity given them by the appearance of the monster yesterday morning in his old hunting ground near the Newcome Buoy. On this occasion it did not prove a happy hunting ground to him, for the doughty whalers, goaded on to revenge, took more careful aim than formerly, and the harpooner in the steam launch was at last fortunate in lodging a harpoon in the fish’s neck, which success was immediately made known by the hoisting of an empty coal bag in lieu of a “jack.”

The two rowing boats, on seeing the signal, at once roved up to the assistance of their more fortunate brother. On its being known that a harpoon had been made fast those who observed it expected to see a mighty commotion, but were vastly disappointed, as his majesty took the matter very calmly. He proceeded to swim down the river very quietly at first, but, as showing that he was wounded, blood was observed to be mingled with the spray which he threw up when he rose to blow, which he did every few minutes. The two rowing boats were not long in getting alongside the launch, and were taken in tow so as to cause a greater drag, and thus retard the speed of, the whale. The launch kept very close to the whale, as it was not necessary to pay out much line on account of the shallowness of the water.

After rounding the Castle, one of the boats — a six-oared one — pulled ahead and lodged another harpoon by way of a reminder that now they had got him, and they intended to walk into him. This second harpoon had apparently made itself severely felt, as the whale made desperate efforts to free itself, lashing furiously with its tail and darting hither and thither at a great rate. At this time the excitement was intense, great crowds lining every available part from which a good view could be obtained. It was calculated that there were about 2000 spectators along the Esplanade. By and by he settled down to a more steady pace, and went bowling along at a considerable speed. The chase was followed by a great fleet of all kinds of boats, filled with people eager to see the sport, large sums being in some instances given as hire for boats and men. Some of these reported on their return that they had followed the. chase as far as the Horse-Shoe Buoy ; that at that time the whale seemed to be getting quite lively and gaining strength. It was noticed that after spouting out a considerable quantity of blood a large piece of some black substance, possibly clotted blood, was thrown up. and that after that the spray was quite clear, and the old fellow apparently himself again.

About this time the boat commanded by Captain Gellatly of the Chieftain, ranged alongside, and though the whole body of the animal was in full view and within easy range, a harpoon aimed at it went gracefully over the side. It is stated that one tug’s assistance was declined with thanks. After that, however, another, the Iron King, proceeded to act the good Samaritan, and assist in towing up both boats and whale, when captured. Unfortunately for those who could not go in boats their view of the contest was very limited on account of a heavy haze hanging over the river.

About one o’clock this morning the steam launch returned to Dundee, the crew reporting that they had lost sight of the boats and the whale when darkness set in, and that when they started for home there was no trace to be seen of either.

From our Broughty Ferry correspondent we learn that, between nine and ten o’clock last night, the whale was still lively, with the two harpoons firmly fixed in it, and its captors holding on, with every hope of being soon able to land the monster.

Dundee Courier, 1st January 1884

Notes

In November 1883, a humpback whale swam into the Tay estuary, probably in pursuit of the shoals of herring to be found there. This intelligent and playful beast spent the following weeks in the area, entertaining crowds of onlookers and harming nobody – apart from nearly overturning a boatload of workers on the new Tay Bridge after an accidental collision.

But the whale had made a spectacularly poor choice of playground. Dundee was the country’s foremost whaling port – whale oil being used in the processing of jute in the city’s mills – and the whole fleet was in harbour for the winter. It didn’t take long for the whalers to have a go at the prize that had appeared on their own doorstep.

But for weeks, all their attempts to kill the unfortunate beast met with failure. A succession of local newspaper stories told how the whale seemed almost to taunt his pursuers, whether “giving a grin and sinking below the water” on their approach, or appearing to to “salute his friends the whalers” on Christmas Day. On one occasion, a flotilla of boats was sent upriver when a passing rail passenger reported the whale beached in Invergowrie Bay. When they got there, they discovered that the “whale” was actually a large black rock!

Just after Christmas, a local wag sent the Dundee Courier this account of “the Whale Interviewed by his Mother on his Exploits in the River Tay”:

Oh! where have you been, my son, my son?

We have not met since the morn was young.

“I left the North, good mother, to see

The whaling fleet in bonnie Dundee.”Oh! why went you tbere, my son, my son,

Within the range of their banging gun?

“Fear not, mother, ’twas only a lark,

I reckoned they would shoot wide of the mark.”Ah! Finny, my boy, is it not vile,

They do so thirst for our precious ile?

“Yes, mother, for our good blubber they pine,

But I took care they didn’t get mine.”Pray, tell me, did they not chase you, dear,

With harpoons, lances, and such like gear?

“What if they followed me, don’t despond,

Chasing’s not catching, mother fond.They follow’d me up, they follow’d me down,

In view of gaping folk of the town;

But I, when they thought to take sure aim,

Skedaddled, and sent them ‘swearin’ hame.'”Go never again, my son, my son,

Rest content with the laurels you’ve won;

“Trust me, mother, they may know about bales —

I’m blowed if they know as much about whales.A party was sent the other day

To do for ma slick in Cowrie’s Bay;

My eye! they peppered it hot on poor me,

Then found it was only a rock. He! he!”

But the whale’s luck could not last forever. On the last day of the year, a harpoonist finally got a shot on target. Watched by a huge crowd, both onshore and afloat, the whalers closed in on their prey. Two more harpoons hit home, and the stricken creature was soon swimming out to sea, dragging two six-oared rowing boats, a steam launch and a steam tug behind him.

The story was not over yet, though. The unfortunate whalers spent an uncomfortable hogmanay night being towed this way and that across outer reaches of the Firth of Tay. Two of the three lines attached to the whale were snapped by his violent thrashings during the night. The whalers, having run out of more conventional ammunition, fired iron bolts and marlinspikes at their quarry, but without apparent effect. Finally, at 8:30 the next morning, the final line gave way and the whale swam off to freedom, leaving the whalers to return empty-handed to Dundee.

Sadly, the many wounds inflicted upon the whale would prove fatal. A week later, the body of the whale was found by fishermen floating off Gourdon, about forty miles along the coast from Dundee. Gleefully, they hauled their prize onshore, whence it was taken to nearby Stonehaven.

A host of sightseers came to see the grounded leviathan, and it soon became clear that the beast might prove useful as more than a source of blubber. When the dead creature was put up for auction later in the week, the winning bidder was Dundee showman John Woods, who paid a princely £226 for it (the equivalent of more than £10,000 in today’s money).

A tug was engaged to tow the remains of the whale back down the coast to Dundee, where it arrived the following night. Thousands watched as a crane lifted the whale out of the water onto two heavy-duty lorries, which were promptly crushed under the 16½ ton weight. It took a specially strengthened bogie, 20 horses, and 26 hours to move the whale just half a mile to Mr Woods’ yard.

Once there, he could begin to recoup on his investment. Members of the public came from all over the area to see the whale. Admission cost sixpence or a shilling, depending on time of day; photographs and other mementoes were on sale; for three shillings you could get your own photo taken sitting in the whale’s mouth. 12,000 visitors came on the first day alone.

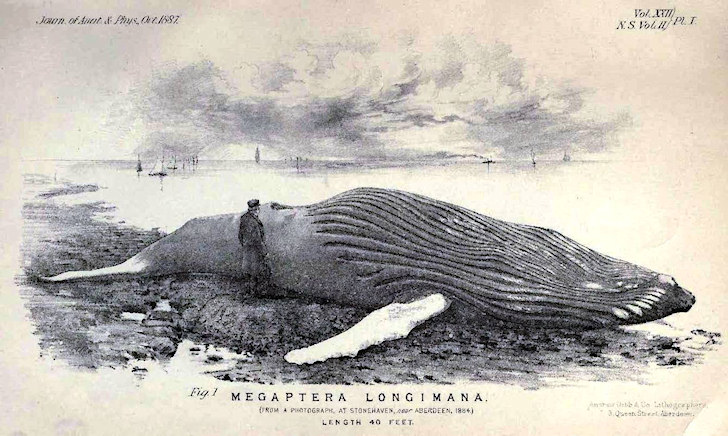

After three weeks of public exhibition, Professor Sir John Struthers of Aberdeen University (wearing a top hat in the picture left) was invited to dissect the whale in the interests of science. The stench of the rotting corpse must have been unbearable, but the Professor carried out his task, watched by more paying customers and accompanied by a local military band.

After three weeks of public exhibition, Professor Sir John Struthers of Aberdeen University (wearing a top hat in the picture left) was invited to dissect the whale in the interests of science. The stench of the rotting corpse must have been unbearable, but the Professor carried out his task, watched by more paying customers and accompanied by a local military band.

Once the Professor had removed the soft tissues and most of the skeleton, the remainder was embalmed and fitted around a wooden frame. The stuffed whale was then taken on a national tour, visiting Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Liverpool, London and Manchester before returning to Dundee in the summer. There, Professor Struthers was able to complete the dissection, removing the skull and remaining bones.

According to the Aberdeen Journal of 26th January 1884, a familiar figure was present at the dissection:

In the course of the dissecting operations an amusing diversion was caused by a long-haired gentleman in a black surtout and slouched hat calling the attention of the spectators to a poem, apropos of the whale, of which he proclaimed himself the author, and which he proceeded to recite with much gusto. He afterwards announced that the poem could be obtained on payment of the sum of one penny, and condescendingly sold a few copies at that figure. There was a good deal of “Silvery Tay” in the poem.

Eventually the complete skeleton was cleaned, rearticulated, and sent to hang in Dundee’s Albert Institute. It still hangs there today, accompanied by a copy of McGonagall’s poem.

Further Reading

- Professor Struthers and the Tay Whale – The story of the whale and the man who dissected him

- Tay Whale Skeleton – The remains of the Tay Whale, now on display in Dundee’s McManus Museum

Books

- The Winter Whale – Nature writer Jum Crumley’s version of the whale’s story

It must have been a sight most afeared,

indeed many would say ‘this is rather weird!’

To see a whale cut open, diseccted, and flailed,

after those poor unfortunate whalers had failed.

Indeed in a top hat the surgeon was clad

and in his heart he surely felt glad

he laughed as he sliced, and gaily he danced

this was because he was a man of science.

He also wore britches, this much was true,

and an expensive white shirt as he was well-to-do.

He really was very well presented

which many jealous peoples surely resented.

This man of science was so learned

that deep in his heart a lust for knowledge burned

And so he resolved without fail so they say

To dissect the whale from the Silvery Tay.