Good people of high and low degree,

I pray ye all to list to me,

And I’ll relate a terrible tale of the sea

Concerning the unfortunate steamer, Mohegan,

That against the Manacles Rocks, ran.

’Twas on Friday, the 14th of October, in the year of ninety-eight,

Which alas! must have been a dreadful sight;

She sailed out of the river Thames on Thursday,

While the hearts of the passengers felt light and gay.

And on board there were 133 passengers and crew,

And each one happier than another seemingly to view;

When suddenly the ship received some terrible shocks,

Until at last she ran against the Manacles Rocks.

Dinner was just over when the shock took place,

Which caused fear to be depicted in every face;

Because the ship was ripped open, and the water rushed in,

It was most dreadful to hear, it much such a terrific din.

Then the cries of children and women did rend the air,

And in despair many of them tore their hair

As they clung to their babies in wild despair,

While some of them cried- ‘Oh, God, do Thou my babies spare!’

The disaster occurred between seven and eight o’clock at night,

Which caused some of the passengers to faint with fright;

As she struck on the Manacles Rocks between Falmouth and Lizard Head,

Which filled many of the passengers’ hearts with dread.

Then the scene that followed was awful to behold,

As the captain hurried to the bridge like a hero bold;

And the seamen rushed manfully to their posts,

While many of the passengers with fear looked as pale as ghosts.

And the poor women and children were chilled to the heart,

And crying aloud for their husbands to come and take their part;

While the officers and crew did their duty manfully,

By launching the boats immediately into the sea.

Then lifebelts were tied round the women and children

By the brave officers and gallant seamen;

While the storm fiend did laugh and angry did roar,

When he saw the boats filled with passengers going towards the shore.

One of the boats, alas! unfortunately was swamped,

Which caused the officers and seamens’ courage to be a little damped;

But they were thankful the other boats got safely away,

And tried hard to save the passengers without dismay.

Then a shriek of despair arose as the ship is sinking beneath the wave,

While some of the passengers cried to God their lives to save;

But the angry waves buffetted the breath out of them,

Alas, poor sickly children, also women and men.

Oh, heaven, it was most heartrending to see

A little girl crying and imploring most piteously,

For some one to save her as she didn’t want to die,

But, alas, no one seemed to hear her agonizing cry.

For God’s sake, boys, get clear, if ye can,

Were the captain’s last words spoken like a brave man;

Then he and the officers sank with the ship in the briny deep,

Oh what a pitiful sight, ’tis enough to make one weep.

Oh think of the passengers that have been tempest tossed,

Besides, 100 souls and more, that have been lost;

Also, think of the mariner while on the briny deep,

And pray to God to protect him at night before ye sleep.

The Wreck of the Mohegan

Great Loss of Life

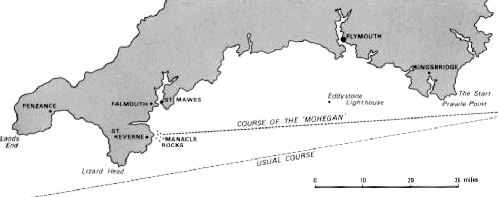

The wreck of the steamship Mohegan, which was briefly reported in The Times of Saturday, proved to be a terrible disaster. The Mohegan (formerly named Cleopatra), a fine cargo and passenger steamship belonging to the Atlantic Transport Company, left the Thames on Thursday afternoon bound for New York. She carried 53 saloon passengers, and the total number of persons on board is officially stated to have been 166. As this was her return voyage she was light in cargo, and her hull was high out of the water. On Friday evening the Lizard peninsula came in sight, and just as darkness came on the passengers assembled in the saloon for dinner. Between half-past 6 and 7 o’clock – witnesses vary. in their statements as to the precise time — a grating sound was heard, and this was quickly followed by crashing noises, as if the bottom of the ship were being torn out by jagged rocks. From some unaccountable cause the Mohegan had been steered direct on to a ledge of rocks forming part of the Manacles reef. At this point of the coastline the rocks are particularly bold, and the ridge, which juts out for a mile-and-a-half into the sea, can be seen for many miles when exposed by receding tides. At the southern extremity of the ridge there is a bell buoy, and the safe passage for vessels lies a good deal to the south of this. But neither this safeguard nor the brilliant lights of St. Anthony at the entrance to Falmouth Harbour and the Lizard availed to keep the Mohegan away from the locality. It was a clear night, although the darkness was intense. There is nothing to explain why the vessel was so far out of her proper course, nor is there likely to be any adequate explanation, as the officers, who alone could furnish one, have perished. It is stated that she ought to have been ten or 15 miles from the land.

The particular ledge of rocks on which the Mohegan struck bears the name of Varais, and is situated about a quarter of a mile inside the bell buoy. Had this ledge been avoided, the vessel would probably have run clear into a cove some little distance away from the village of Porthoustock, the lifeboat station. According to accounts of the disaster she was steaming at over 13 knots at the time when she struck the rocks. When the first alarming sounds were heard passengers rushed up on deck from the saloon, and the greater part of the crew quickly followed them. Signals of distress were shown, and there is a story that the shrieks from the despairing passengers were heard four miles inland. Great rents must have been made in the bottom of the hull, for the inrushing waters lifted up the metal plates forming the flooring of the engine-room and rose three foot in less than a minute. The electric light appliances were soon submerged, and the whole vessel was plunged in darkness. This added greatly to the horror of the situation. The huge vessel was swaying in the surf, continually washed by big breakers, and the grinding of the rocks in contact with the bottom added continually to the fright of the wretched passengers, who were huddled together on the deck hoping for means of deliverance. Immediately after the impact the fore part of the ship began to settle, and there was a list to one side. Some of the crew stood by the lifeboats, of which there .were eight on board, but there seems to have been delay in getting them afloat. As a matter of fact, two only were launched before the foundering of the ship precipitated the mass of human beings who were on the deck into the sea. The want of promptitude in getting the life-boats out was probably due to the inexperience of the crew in the matter. Most of the men were fresh for this voyage, and one of them stated that they ware ignorant of the boat stations. Several survivors, however, credit them with coolness and courage in the time of peril Attention was at once paid to the women and children, who were as far as possible got into the lifeboat first. The captain is stated to have given his orders clearly and to have paid special heed to the despatch of the lifeboats. He was last seen jumping overboard with others who were on deck at the time of the lurch which sent everybody into the water. Prior to this another lifeboat was cleared with a good load of people, but this was swamped and capsized and only two or three of its occupants were rescued. The others were discovered dead under the overturned boat.

By dint of arduous exertion the first boat was kept afloat and clear of the wreckage, and her load of human beings was safely transferred to the Porthoustock lifeboat. Twenty minutes at the most elapsed between the striking of the vessel on the rocks and her foundering. During that time scenes of pathos occurred on board the sinking ship, although there was an absence of anything like panic. Mothers agonized entreaties for the safety of children, the heartbreaking separation of members of families, and the severance of comrades were incidents which have burnt themselves into the memory of all who witnessed and have lived to narrate them. After the ship listed to one side she lurched suddenly and very heavily to the other and many persons were hurled into the sea. For a few minutes after this awful plunge the sea around the sunken ship was alive with straggling and shrieking people, but gradually the cries died away, and when the last survivors were taken from their perilous positions on the rigging of the submerged vessel the only sounds audible were the roar of the breakers and the rush of the wind. At about 7 o’clock rockets from the Porthoustock Lifeboat Station gave the alarm to the district. Some of the crew of the lifeboat live at a distance, but by half-past 7 o’clock the boat was launched. A ship’s lifeboat, bottom up with men clinging to it and people inside it gradually suffocating, was the first object to demand their attention. After dragging all but one of those clinging to the boat’s bottom into the lifeboat and having to allow one poor fellow to remain, the lifeboatmen turned the boat over and found that the greater portion of those who had sought safety in it were dead. Of the two or three who were still alive, one lady, Mrs. Grandin, was so crushed that she had to be cut out from the boat. Although every care was taken of her she died before the lifeboat got back to Porthoustock. Two men hanging on to wreckage were next rescued and then the lifeboat encountered the other a ship’s boat with 22 persons. The ship’s boat was waterlogged and her passengers in a perilous condition, and they were taken into the lifeboat. Miss Noble, a lady passenger, was found clinging to a plank and was picked up. The lifeboat returned with 26 survivors and having landed them put out again. They then found the Mohegan. Only the masts and the funnel were above water. Sixteen persons, including one woman, Mrs. Piggott, the assistant stewardess, were found clinging to the rigging. Two or three hours were spent in the perilous task of taking these off one by one. Both the rescued and rescuers alike received attention on reaching the shore. One or two other lifeboats had been called out, but they naturally did not arrive until late. As far as is known no survivors or bodies were picked up by any other lifeboat than the Porthoustock boat. One man named Maule was picked up by a Falmouth life-boat tug after having been over seven hours in the water.

The Times, 17th October 1898

Notes

The wreck of the Atlantic Transport Line steamship Mohegan is one of the enduring mysteries of British maritime history. How did a brand new ship on a clear calm night steam straight into a set of rocks that every sailor on board would have known about? Whatever the reason, it cost the lives of 106 men, women and children.

The short history of the Mohegan was not a happy one. Originally named the Cleopatra, her construction had been halted by a strike in the shipyard. Once the strike had been resolved, completion of the ship was rushed in order to avoid ruinous penalty clauses in the builder’s contract. As a result, she was delivered with serious faults that soon became apparent. Her maiden voyage to New York was a nightmare – beset by leaks in the hull, and problems with the boilers and the plumbing. Once she’d limped back home, it took six weeks of repairs to render her fit for purpose. The newly fixed up ship would bear a new name to fit her owners’ house style of nomenclature, the new name Mohegan would soon be heard around the world.

The short history of the Mohegan was not a happy one. Originally named the Cleopatra, her construction had been halted by a strike in the shipyard. Once the strike had been resolved, completion of the ship was rushed in order to avoid ruinous penalty clauses in the builder’s contract. As a result, she was delivered with serious faults that soon became apparent. Her maiden voyage to New York was a nightmare – beset by leaks in the hull, and problems with the boilers and the plumbing. Once she’d limped back home, it took six weeks of repairs to render her fit for purpose. The newly fixed up ship would bear a new name to fit her owners’ house style of nomenclature, the new name Mohegan would soon be heard around the world.

At first, all went well. She left London on 13th October carrying a cargo of spirits, beer and antimony and 53 well-to-do passengers. The ship carried no steerage passengers, instead having stalls for 700 cattle and “an improved system of sanitation rendering the cattle carrying quite free from annoyance to passengers.” A letter from the Chief Engineer that came ashore with the Thames pilot after five hours of steaming reported only a few minor teething troubles – nothing to compare with the cruise of the Cleopatra.

The ship passed around the coast of Kent and set off down the English Channel. However, as she passed the Eddystone, she inexplicably steered a course several points north of that she should have followed – a collision course with the Manacles Reef!

The passengers were just sitting down to dinner at seven o’clock when the ship hit the rocks with a fearful crash. Water gushed in, soon swamping the generators and plunging the ship into darkness. Chaos ensued as crew and passengers crowded onto the deck and the captain gave the order to abandon ship.

Great difficulty was experienced in launching the lifeboats. The crew was new to the ship and unfamiliar with the boat drill, the ropes and blocks were new and stiff, and the ship had already heeled over to an angle. The tradition of “women and children first” was adhered to, but rather too closely: the first boat had only four men in it to handle it, and it was soon capsized with the loss of most on board. Only two boats were launched before a sudden lurch by the ship hurled most of those on board into the sea. A lucky few were able to cling to the masts and rigging, which stood clear of the water (and remained that way for some days after the wreck) until they were rescued hours later.

Great difficulty was experienced in launching the lifeboats. The crew was new to the ship and unfamiliar with the boat drill, the ropes and blocks were new and stiff, and the ship had already heeled over to an angle. The tradition of “women and children first” was adhered to, but rather too closely: the first boat had only four men in it to handle it, and it was soon capsized with the loss of most on board. Only two boats were launched before a sudden lurch by the ship hurled most of those on board into the sea. A lucky few were able to cling to the masts and rigging, which stood clear of the water (and remained that way for some days after the wreck) until they were rescued hours later.

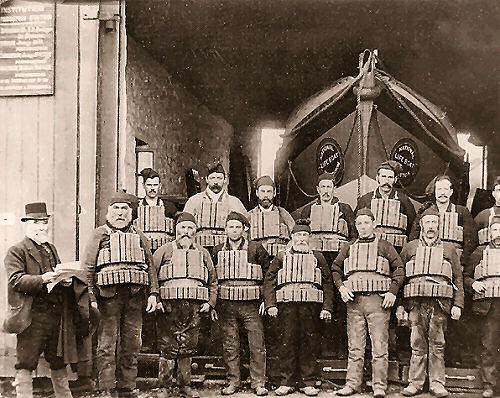

On shore, the alarm was quickly raised and the lifeboat crew at nearby Porthoustock (pictured below) had launched their vessel within half an hour of the foundering of the Mohegan. However, the night was a dark one, and it was only by the guidance of rockets fired from the shore that they were able to find their way to the wreck. The darkness and the rising swell made their task most dangerous, but several trips out to the wreck were made nonetheless. As a result, some 50 lives were saved.

One of the last people to be plucked from the waves was a cattleman named George Maule, who gave this account of the wreck to The Times:

The Mohegan left London on Thursday. All went well until about 7 o’clock on Friday evening, when most of the passengers were at dinner. The steamer was going at full speed, when the passengers heard a big crash as if there was a collision. On rushing on deck they found their vessel was on the rocks. Orders were immediately given to lower the boats. The crew behaved like heroes. The captain stood on the bridge and the greatest order existed among the officers and crew. The steamer immediately began to settle down by the head. Meanwhile two boats were launched the women being sent away first. The vessel filled rapidly. I secured a lifebelt and jumped overboard in company with Mr. Couch, the chief officer. When in the water Mr. Couch made me take off my coat and boots. Soon after we got parted from each other. When leaving a little girl begged me most piteously to save her, as she “did not want to die yet,” but I was powerless. On getting into the water I fortunately found a bit of plank floating, and to it I clung until I was picked up seven hours afterwards by the famous tug and lifeboat. I could not have lasted much longer. I cannot tell how the accident happened. It was a very clear night. The captain was an experienced sailor. Indeed, he was commodore of this line.

One of the lifeboatmen, Bentley More, told this story in a letter to his sister:

The first shipload we came to was capsized, bottom up, but we threw a grapnel and righted her. One man jumped into the boat (a smart man, he ought to be rewarded), and the boat was full of water. I and one or two others caught hold of the boat and the man in the boat got one woman out, but she died soon afterwards. The next boat was all right, but the people were terribly scared; we took them all in, women and children and men. One woman threw her arms round my neck; they were mad with joy. Then we picked up all we could, some on lifebelts and some on wreckage.

The last was Miss Noble, a girl on a piece of wreckage. She had been in the sea three hours, and, mind you, a very nasty sea. All she said was “Just chuck me a rope,” and we hauled her on board and she just shook the water off her and sat down in the most unconcerned way. We got ashore after a devil of a pull; we had so many in the boat and we took two hours rowing home.

Dark rumours soon surrounded the wreck. Several locals claimed to have seen a man get out of the first lifeboat to be brought ashore and run inland never to be seen again. It was said that this was the ship’s captain, captain Griffith (pictured right) reputedly a shareholder in the company who had deliberately wrecked the boat in order to collect on the insurance. This theory doesn’t really hold water, as the ship was brand new and insured for £38,000 less than was paid for her. The official inquest was unable to determine any reason for the wreck, as none of the ship’s officers had survived to be questioned about it.

Dark rumours soon surrounded the wreck. Several locals claimed to have seen a man get out of the first lifeboat to be brought ashore and run inland never to be seen again. It was said that this was the ship’s captain, captain Griffith (pictured right) reputedly a shareholder in the company who had deliberately wrecked the boat in order to collect on the insurance. This theory doesn’t really hold water, as the ship was brand new and insured for £38,000 less than was paid for her. The official inquest was unable to determine any reason for the wreck, as none of the ship’s officers had survived to be questioned about it.

Bodies were collected at St Keverne’s church, and many were buried in a mass grave there soon afterwards. Survivors were put up by the local villagers until they were sufficiently recovered to travel. Some of the ship’s alcoholic cargo washed up on the beach, and this was accommodated by the villagers too! A stained glass window was erected in St Keverne’s church bearing the inscription:

To the Glory of God and in memory of the 106 Persons who perished in the wreck of the SS Mohegan on the Manacle Rocks, October 14th 1898. This window was erected by the Atlantic Transport Comp., owners of the vessel.

Today, the wreck of the Mohegan is a popular destination for scuba divers. Its location close to the coast and interesting story making it doubly attractive. Apparently the ship’s boilers can still be clearly seen after more than a century on the sea bed.

Further Reading

- Steamship S.S. Mohegan – Lots of information about the ship and her fate, from a website dedicated to the Atlantic Trasport Line

- The Shipwreck of The Mohegan – The story told from the viewpoint of local people by the St Keverne local history society. They even have some sound recordings of witnesses to the wreck

- Wreck Report for ‘Mohegan’, 1898 – The official Board of Trade report on the wreck

- SS Mohegan – Wikipedia article on the ship and its wreck

- Mohegan – An account of the wreck aimed primarily at scuba divers

- SS Mohegan [+1898] – Data on the ship and its wreck

Books

- The Atlantic Transport Line, 1881-1931 – History of the company that owned the Mohegan